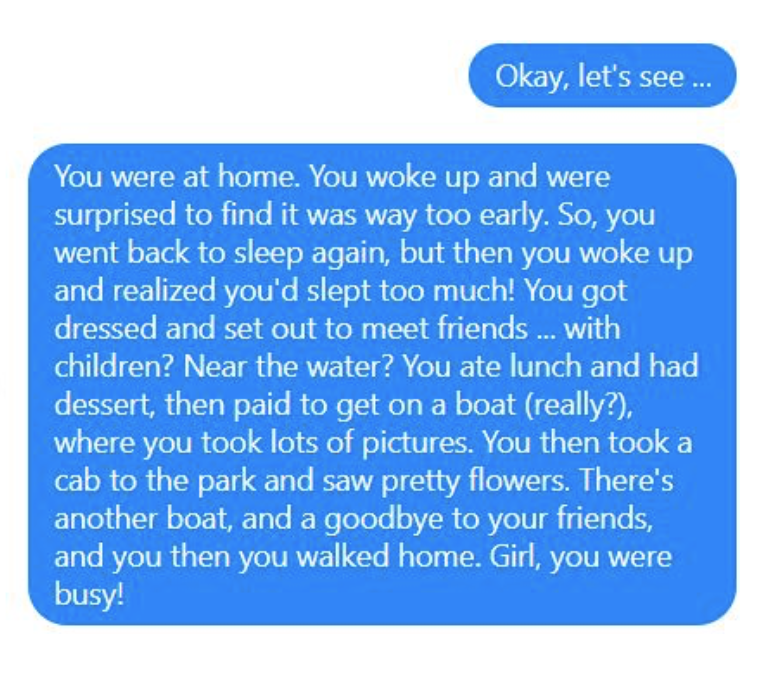

This morning, my guy texted me:

![]()

And I texted back:

![]()

He said, “Good morning! It’s a beautiful day. Love you!”

And I wrote back, “Good morning! I’ve got a song in my heart. Mwah! Love you, too.”

The texter and I are close. We know each other, so our emoji-only conversation made sense to us. The message is unambiguous enough that even an outside observer might have interpreted it similarly. But that’s not always the case when it comes to emoji. Although familiarity and context made this little exchange successful, research shows that emoji interpretation varies, particularly across different cultures.

The Cultural Associations of Common Emoji

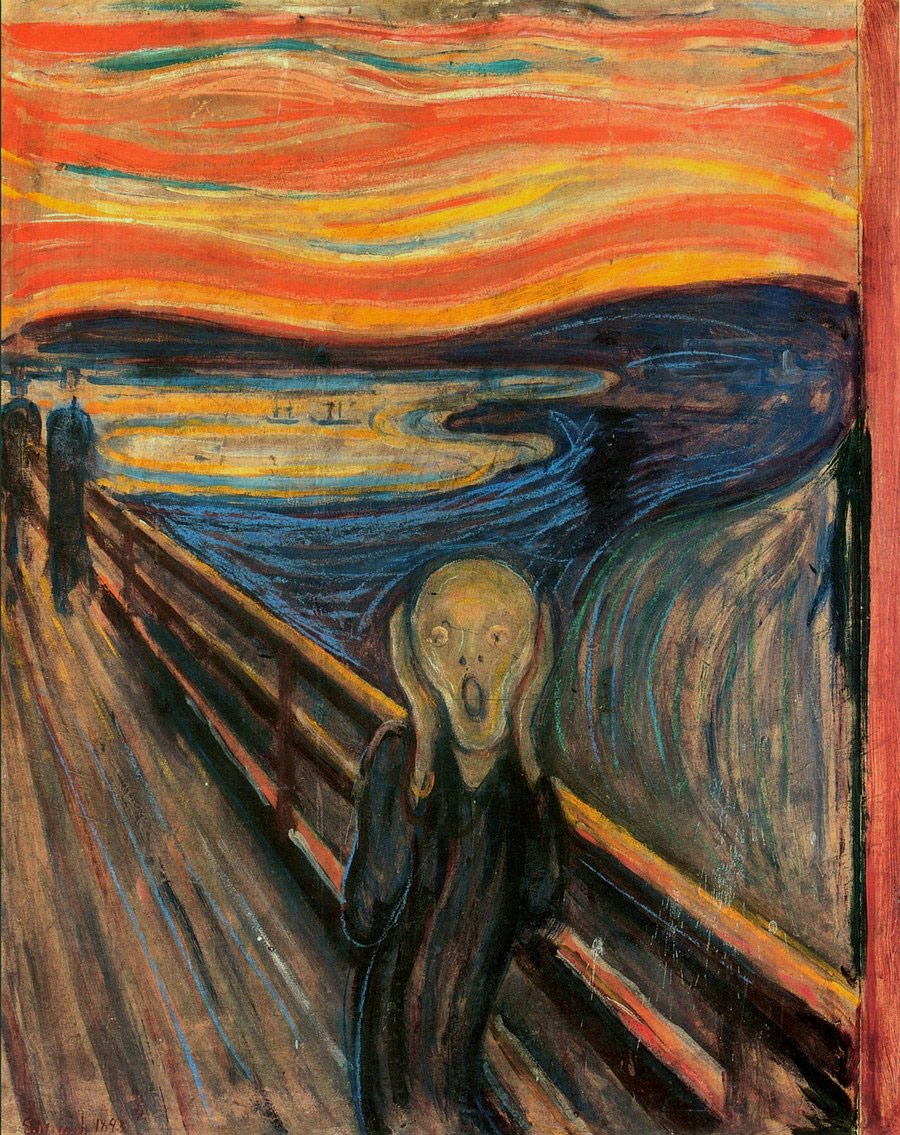

You’d think that pictures are a universal concept. Especially very simple pictures meant to convey an idea or emotion. But ask any visual artist and they’ll tell you that there are as many ways to interpret a piece of visual art as there are people to view it. Take Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s famous painting, The Scream.

It inspired this:

The emoji is intended to convey fear. (In fact, it’s name is Face Screaming in Fear.) Those who know the Munch painting might easily see this emoji as conveying exactly that. Others might call to mind Kevin McCallister in the movie Home Alone. But still others view it as an expression of shock or amazement rather than fright.

Fun fact: The actual intention of The Scream is much more layered than a “scream of fear” would suggest. Munch’s own description is: “I was walking down the road with two friends when the sun set; suddenly, the sky turned as red as blood. I stopped and leaned against the fence, feeling unspeakably tired. Tongues of fire and blood stretched over the bluish black fjord. My friends went on walking, while I lagged behind, shivering with fear. Then I heard the enormous infinite scream of nature.”

Emojis were supposed to make communication across cultures easier, but the jury’s definitely still out on whether they succeeded. Not only does the appearance of emojis vary across devices, but the way we interpret them also varies depending on where in the world we happened to grow up.

The Pile of Poo is a great example of cultural differences at work. Western cultures might interpret this little character somewhat figuratively (as you might if you were trying to convey that you’d had a crappy day), or even literally (which requires no further explanation.)

In Japan, however, the happy little pile is a way of wishing someone good luck. The Japanese word for poop is unko. Because it happens to start with the same “oon” sound as the Japanese word for luck, a unique culture-specific phenomenon was born. In Japan, you can buy golden poop charms and even candies shaped like . . . well, you get it.

Fun fact: Canadians use the poop emoji more than folks in any other country.

There are other examples of Japanese culture inspiring emojis that most Westerners don’t get, or at least tend to use in a different context. You know the little guy who looks like he’s shedding a single tear?

It’s actually an emoji called Sleepy Face. And that’s not a tear; it’s a snot bubble. This rather, er . . . charming effect comes from Japanese anime, where the snot bubble is often used to paint a comedic picture of a sleepy character.

Here’s another often misinterpreted emoji.

If you live in a Western culture, you might well view this as an expression of anger, especially if you’ve watched enough cartoons where the raving mad character blows steam out of his flaring nostrils. But hold on a minute!

That emoji is named Face With Look of Triumph. It’s intended to convey the sort of derisive snort you might give if you’re #Winning.

The emojis we favor also vary by country. According to a popular 2016 report by SwiftKey:

- Canadians score highest in emoji categories you might typically think of as ‘all-American’ (money, raunchy, violent, sports).

- The French use four times as many heart emojis than speakers of other languages, and it’s the only language for which a ‘smiley’ is not #1.

- Arabic speakers use flower and plant emojis four times more than average.

- Russian speakers are the biggest romantics, using three times as many romance-themed emoji as the average.

- Australia is the land of vices and indulgence according to the emoji data, using double the average amount of alcohol-themed emoji, 65% more drug emoji than average, and leading for both junk food and holiday emoji.

- Americans use more LGBT-themed emojis more than others.

- Americans also lead for a random assortment of emoji and categories, including skulls, birthday cake, fire, tech, meat, and female-themed emoji.

Are emojis a language?

Emojis were designed to be the next evolutionary step from text-based emoticons. Shigetaka Kurita, then an employee at the largest mobile provider in Japan, created them in early 1999. They’re meant to provide an image-based system for expressing abstract ideas or emotions (like laughter, sadness, confusion, or sarcasm) with a single character, similar to Japanese kanji. In fact, the word “emoji” comes from the Japanese e, meaning picture, and moji, which means character.

But are these picture characters a language of their own? Here’s some insight from Grammarly’s 2016 article on the subject:

According to Johanna Nichols, former professor of linguistics at UC Berkeley, the gold standard for distinguishing languages is “mutual intelligibility.” In other words, if a speaker of one language and a speaker of another try to converse, will they understand one another? If the answer is “yes,” the second speaker is using some sort of dialect. If the answer is “no”, that person has created or adopted a new language.

Although the future of emojis is evolving, most experts currently view them as more of a language enhancement than a language proper. Their effect is additive. Still, as the example I provided at the beginning of this article illustrates, it’s possible to have at least rudimentary conversations in emoji.

But I wasn’t quite satisfied that a brief emoji exchange could indicate a capacity for mutual understanding. I wanted to test it further.

An Attempt at Emoji-Only Conversation

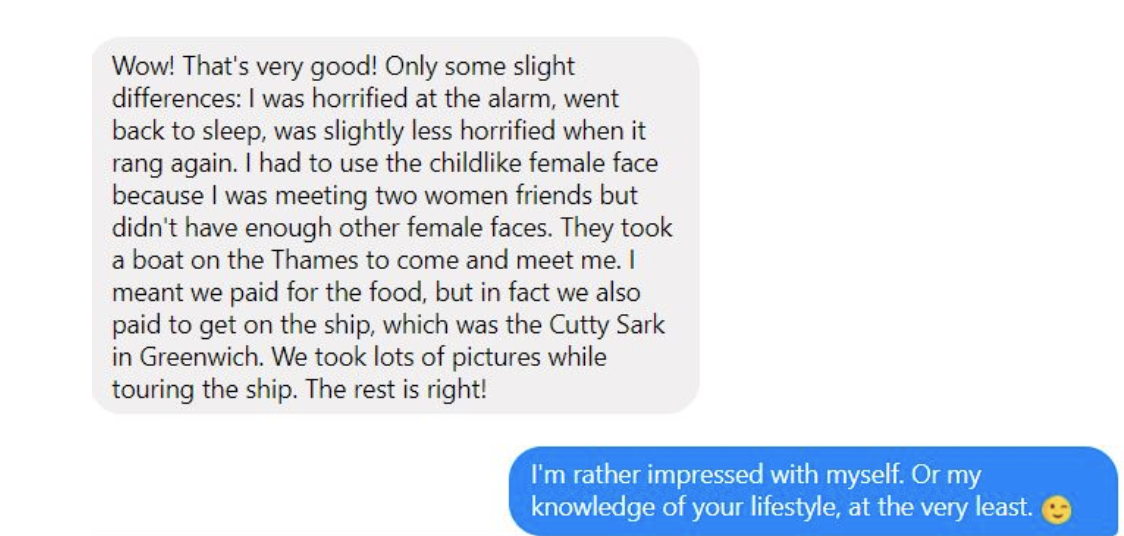

I enlisted a friend to help me explore the idea of an emoji conversation. Would we be able to understand each other in a slightly more complex scenario than a simple good morning?

Esha and I have known each other for over twenty years. We became friends because we haunted the same arts and writing chat room back in the early years of the public Internet. (May Prodigy rest in peace.) Although we’ve been lucky enough to hang out in person just about annually since we’ve known each other, most of our friendship takes place online. I felt that if any relationship could withstand the emojis-only test, this one would.

Esha and I have different cultural backgrounds. She was raised in Hawaii, the child of academic and artistic parents. I was raised in the upper Midwest, the child of working class parents who didn’t bother to graduate from high school. She’s lived in England for about twelve years and is becoming more integrated into that society. I embody Midwest Americana.

I decided that a slightly directed conversation would afford us our best chance for success, so we asked each other questions and then attempted to reply with emoji.

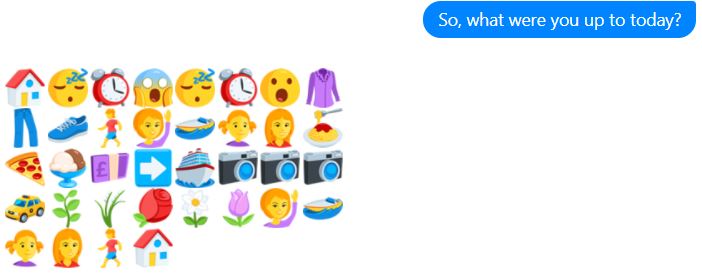

Esha’s emoji answer seemed pretty straightforward to me. Here’s what I guessed:

It turns out I was pretty close!

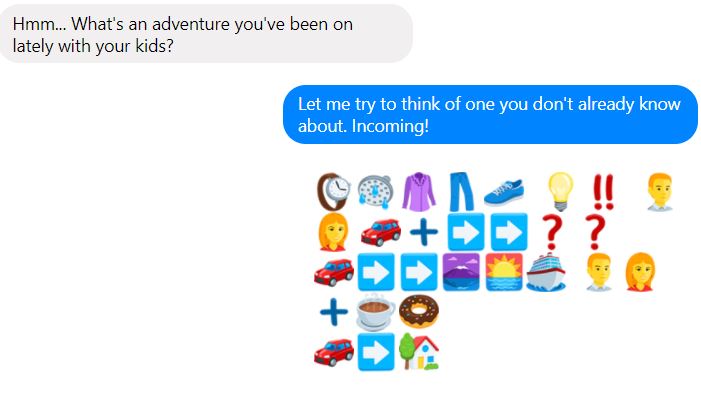

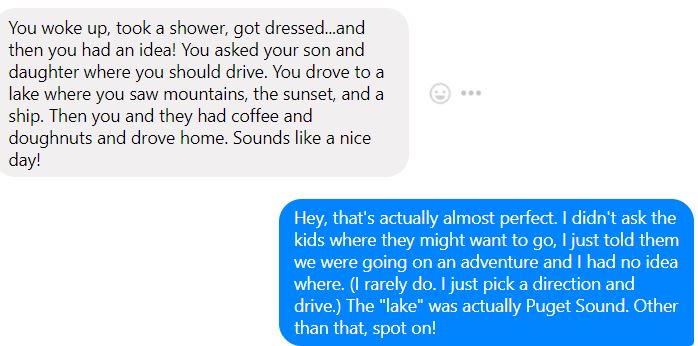

Now, it was my turn to tell an emoji story for Esha. I hoped I could convey ideas through images as well as she had. Here’s how it went down.

And here’s what Esha guessed:

Sidebar: I use “actually” way too often when I write. Good thing I know how to streamline when I proofread. Unfortunately, I didn’t proofread in chat.

Before I set out to have this emoji-only conversation, I was convinced it would fail, and fail comically. But Esha and I know each other well. In hindsight, I might’ve considered picking a more distant (or at least less communicative) friend or acquaintance for my experiment if I wanted to show the challenges of communicating in little digital pictures.

Never fear. Samantha Lee has that covered. For an article in Quartz, she tried communicating solely in emoji for a day. The results weren’t nearly as impressive as mine and Esha’s. She wrote:

By the end of the day, I’d learned a lot—and tested the strength of a few friendships in the process. Texting without words turns out to be a lot like eating soup without a spoon: It’s possible, but not pleasant.

Are emojis nothing more than images that might be interpreted differently by different groups of people, or even different individuals? Or do they have a chance to become universal? Either way, emojis represent a unique cultural phenomenon. Send your friend an emoji-only text today and see what happens.